Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent, unprovoked seizures resulting from abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Affecting people of all ages, genders, and backgrounds, epilepsy is one of the most common neurological conditions worldwide. Seizures can vary significantly in their manifestation, ranging from brief lapses in attention or muscle jerks to severe and prolonged convulsions.

The causes of epilepsy are diverse, including genetic factors, brain injuries, infections, developmental disorders, and structural abnormalities in the brain. Despite advances in medical research, in many cases, the exact cause remains unknown. Diagnosing epilepsy involves a comprehensive evaluation, including a detailed medical history, neurological examinations, and diagnostic tests such as electroencephalograms (EEGs) and brain imaging.

Living with epilepsy poses significant challenges, impacting daily activities, education, employment, and quality of life. Effective management typically requires a combination of medications, lifestyle adjustments, and sometimes surgical interventions. With appropriate treatment, many individuals with epilepsy can lead fulfilling lives, though the condition often requires ongoing medical care and monitoring.

Understanding epilepsy is crucial for improving diagnosis, treatment, and support for those affected by the condition. This introduction will explore the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment options, and strategies for living with epilepsy, highlighting the importance of awareness and comprehensive care in managing this complex disorder.

Table of Contents

Types of Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a complex neurological condition with a wide range of seizure types and syndromes. Understanding the different types of epilepsy is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. Here are the primary types of epilepsy:

1. Focal (Partial) Epilepsy

Focal epilepsy originates from a specific area or focal point in the brain. Seizures can be categorized based on whether the person retains awareness during the seizure.

Focal Aware Seizures (Simple Partial Seizures)

- Symptoms: Involve localized symptoms without loss of consciousness. Symptoms may include muscle twitching, sensory changes (e.g., tingling, visual disturbances), and autonomic symptoms (e.g., sweating, nausea).

- Duration: Typically brief, lasting seconds to minutes.

Focal Impaired Awareness Seizures (Complex Partial Seizures)

- Symptoms: Involve a loss or alteration of consciousness, often accompanied by automatisms (repetitive movements such as lip-smacking, picking at clothes).

- Duration: Usually lasts one to two minutes, followed by confusion or disorientation.

2. Generalized Epilepsy

Generalized epilepsy involves seizures that affect both hemispheres of the brain simultaneously. These seizures often result in a loss of consciousness and can vary in their presentation.

Absence Seizures (Petit Mal)

- Symptoms: Characterized by brief, sudden lapses in consciousness, typically lasting 5-10 seconds. The person may stare blankly, often without any motor activity.

- Occurrence: Common in children and may happen multiple times a day.

Tonic-Clonic Seizures (Grand Mal)

- Symptoms: Begin with a tonic phase (muscle stiffening) followed by a clonic phase (rhythmic jerking of the limbs). The person usually loses consciousness.

- Duration: Typically lasts 1-3 minutes, followed by a postictal phase of confusion and fatigue.

Myoclonic Seizures

- Symptoms: Sudden, brief jerks or twitches of muscles or muscle groups. Consciousness is usually not impaired.

- Occurrence: Often occur shortly after waking up.

Atonic Seizures (Drop Attacks)

- Symptoms: Sudden loss of muscle tone, leading to a collapse or fall. Consciousness is briefly impaired.

- Risk: High risk of injury due to sudden falls.

Tonic Seizures

- Symptoms: Sudden stiffening of muscles, often causing the person to fall if standing.

- Duration: Typically brief, lasting less than 20 seconds.

Clonic Seizures

- Symptoms: Repetitive, rhythmic muscle contractions and relaxations (jerking movements).

- Duration: Lasts a few seconds to a minute.

3. Combined Generalized and Focal Epilepsy

Some individuals have seizures that start as focal but then spread to become generalized. These are known as focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures.

- Symptoms: Initial localized symptoms (such as focal aware or impaired awareness seizures) followed by generalized tonic-clonic activity.

- Duration: The initial focal phase can last seconds to minutes, with the generalized phase lasting 1-3 minutes.

4. Epileptic Syndromes

Specific epilepsy syndromes are defined by a unique combination of seizure types, age of onset, EEG findings, and other clinical features. Here are a few examples:

Childhood Absence Epilepsy

- Onset: Typically begins between ages 4 and 10.

- Symptoms: Frequent absence seizures with brief staring spells.

- Prognosis: Many children outgrow the condition by adolescence.

Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME)

- Onset: Typically begins in adolescence.

- Symptoms: Myoclonic jerks, often upon waking, and sometimes generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

- Prognosis: Generally lifelong but can be well-managed with medication.

Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome

- Onset: Typically begins in early childhood.

- Symptoms: Multiple seizure types, including tonic, atonic, and atypical absence seizures, often accompanied by intellectual disability.

- Prognosis: Difficult to control; requires comprehensive treatment.

5. Reflex Epilepsy

In reflex epilepsy, seizures are triggered by specific stimuli or activities.

- Triggers: Common triggers include flashing lights (photosensitive epilepsy), reading, or specific sounds.

- Management: Avoidance of triggers and medication to control seizures.

Understanding the various types of epilepsy and their unique characteristics is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management. Each type of epilepsy may require different treatment approaches and strategies to optimize the quality of life for individuals affected by this condition. Ongoing research continues to enhance our understanding of epilepsy and improve treatment options.

Symptoms of Epilepsy

Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent seizures, which are sudden bursts of abnormal electrical activity in the brain. The symptoms of epilepsy vary widely depending on the type of seizure and the regions of the brain affected. Here are the primary symptoms associated with different types of seizures in epilepsy:

1. Focal (Partial) Seizures

Focal seizures originate in one specific area of the brain and can be categorized based on whether consciousness is affected.

Focal Aware Seizures (Simple Partial Seizures)

- Symptoms:

- Motor symptoms: Twitching or jerking in one part of the body, such as an arm or leg.

- Sensory symptoms: Tingling, numbness, or a feeling of “pins and needles”; unusual smells, tastes, or sounds.

- Autonomic symptoms: Changes in heart rate, sweating, nausea, or a feeling of butterflies in the stomach.

- Psychic symptoms: Sudden, unprovoked feelings of fear, déjà vu, or jamais vu.

- Consciousness: Remains intact during the seizure.

- Duration: Typically lasts a few seconds to a couple of minutes.

Focal Impaired Awareness Seizures (Complex Partial Seizures)

- Symptoms:

- Altered awareness: Confusion or a dazed state.

- Automatisms: Repetitive movements such as lip-smacking, chewing, hand-wringing, or walking in circles.

- Sensory and emotional symptoms similar to focal aware seizures.

- Consciousness: Impaired or altered during the seizure.

- Duration: Usually lasts 1-2 minutes, followed by a period of confusion or disorientation.

2. Generalized Seizures

Generalized seizures involve both hemispheres of the brain and often result in a loss of consciousness.

Absence Seizures (Petit Mal)

- Symptoms:

- Brief lapses in awareness, often described as “staring spells.”

- No convulsions or significant motor activity.

- Possible subtle body movements such as blinking, lip-smacking, or slight head movements.

- Consciousness: Briefly lost or altered.

- Duration: Typically lasts 5-10 seconds.

- Frequency: Can occur multiple times a day.

Tonic-Clonic Seizures (Grand Mal)

- Symptoms:

- Tonic phase: Muscle stiffening, often causing the person to fall.

- Clonic phase: Rhythmic jerking of the limbs and face.

- Loss of bladder or bowel control.

- Biting of the tongue or cheek.

- Consciousness: Lost during the seizure.

- Duration: Typically lasts 1-3 minutes.

- Postictal state: Period of confusion, fatigue, headache, and muscle soreness following the seizure.

Myoclonic Seizures

- Symptoms:

- Sudden, brief, involuntary jerks or twitches of muscles or muscle groups.

- Usually occur in clusters, often shortly after waking.

- Consciousness: Typically not impaired.

- Duration: Lasts just a few seconds.

Atonic Seizures (Drop Attacks)

- Symptoms:

- Sudden loss of muscle tone, leading to a collapse or fall.

- High risk of injury due to sudden falls.

- Consciousness: Briefly impaired.

- Duration: Usually lasts less than 15 seconds.

Tonic Seizures

- Symptoms:

- Sudden stiffening of the muscles, typically in the arms, legs, and back.

- Often occurs during sleep.

- Consciousness: Usually lost or impaired.

- Duration: Typically brief, lasting less than 20 seconds.

Clonic Seizures

- Symptoms:

- Repetitive, rhythmic muscle contractions and relaxations (jerking movements).

- Can affect different muscle groups.

- Consciousness: Usually impaired during the seizure.

- Duration: Lasts a few seconds to a minute.

3. Focal to Bilateral Tonic-Clonic Seizures

Seizures that begin in one part of the brain and spread to both sides, resulting in tonic-clonic activity.

- Symptoms:

- Initial focal symptoms, followed by tonic and clonic phases similar to generalized tonic-clonic seizures.

- Consciousness: Typically impaired.

- Duration: The focal phase can last seconds to minutes, with the generalized phase lasting 1-3 minutes.

The symptoms of epilepsy are diverse and can vary greatly between individuals and types of seizures. Understanding the specific symptoms associated with different seizure types is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management of epilepsy. Early recognition and appropriate treatment can help individuals with epilepsy lead a safer and more fulfilling life.

Causes of Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures, which are caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. The causes of epilepsy can be broadly categorized into genetic, structural, infectious, metabolic, immune, and unknown origins. Understanding the underlying cause is crucial for effective treatment and management. Here are the primary causes of epilepsy:

1. Genetic Factors

- Inherited Conditions: Some types of epilepsy have a genetic basis, where mutations in specific genes are passed down through families. For example, certain forms of childhood epilepsy, like Dravet syndrome, are linked to mutations in the SCN1A gene.

- Genetic Predisposition: Even without a clear single-gene mutation, some individuals may have a genetic predisposition to epilepsy, making them more susceptible to seizures.

2. Structural Causes

- Brain Malformations: Congenital brain malformations, such as cortical dysplasia, can disrupt normal brain activity and lead to epilepsy.

- Head Trauma: Severe head injuries, including those from car accidents, falls, or sports injuries, can cause structural damage to the brain and lead to epilepsy.

- Stroke: Strokes, which result from a disruption of blood flow to the brain, can cause brain damage and subsequently lead to seizures and epilepsy.

- Brain Tumors: Both benign and malignant tumors in the brain can cause abnormal electrical activity, leading to seizures.

3. Infectious Causes

- Infections of the Brain: Conditions such as meningitis, encephalitis, and brain abscesses can cause inflammation and damage to the brain, resulting in epilepsy.

- Parasitic Infections: Neurocysticercosis, caused by the pork tapeworm Taenia solium, is a common cause of epilepsy in developing countries.

4. Metabolic Causes

- Metabolic Disorders: Certain metabolic disorders, such as mitochondrial diseases, can disrupt normal brain function and lead to seizures.

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Severe imbalances in electrolytes, such as sodium or calcium, can trigger seizures.

5. Immune Causes

- Autoimmune Disorders: Some forms of epilepsy are associated with autoimmune conditions where the body’s immune system attacks brain tissue, causing inflammation and seizures. Autoimmune encephalitis is one such condition.

6. Prenatal and Perinatal Causes

- Prenatal Injury: Brain damage occurring before birth, due to factors such as maternal infections, poor nutrition, or oxygen deprivation, can lead to epilepsy.

- Birth Complications: Complications during delivery that result in a lack of oxygen to the baby’s brain (hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy) can cause brain damage and subsequent epilepsy.

7. Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Alzheimer’s Disease: Neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s disease can disrupt normal brain function and lead to seizures.

- Other Neurodegenerative Diseases: Conditions such as Huntington’s disease and multiple sclerosis can also be associated with seizures.

8. Unknown Causes

- Idiopathic Epilepsy: In many cases, no specific cause for epilepsy can be identified. This is referred to as idiopathic epilepsy, which is believed to have a genetic component even if no direct genetic mutation is identified.

Risk Factors

Epilepsy is a complex neurological disorder with various risk factors that can increase an individual’s likelihood of developing the condition. These risk factors can be genetic, environmental, or related to other health conditions. Understanding these risk factors is essential for early identification, prevention, and management of epilepsy.

1. Genetic Factors

- Family History: Having a family member with epilepsy increases the risk of developing the condition due to inherited genetic factors.

- Genetic Mutations: Specific genetic mutations, such as those in the SCN1A gene associated with Dravet syndrome, can directly cause epilepsy.

2. Age

- Infancy and Childhood: Epilepsy is more common in young children, often due to developmental issues or genetic conditions.

- Elderly: The risk of epilepsy increases with age due to factors such as stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, and brain tumors.

3. Prenatal and Perinatal Factors

- Prenatal Brain Injury: Injuries to the brain before birth, such as those caused by maternal infections, poor nutrition, or exposure to toxins, can increase the risk.

- Birth Complications: Complications during delivery, including prolonged lack of oxygen (hypoxia) or trauma, can result in brain injury leading to epilepsy.

4. Brain Injuries and Trauma

- Head Injuries: Traumatic brain injuries, such as those sustained in accidents, sports injuries, or falls, can increase the risk of developing epilepsy.

- Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Repeated concussions, especially in contact sports, can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which is associated with epilepsy.

5. Infections

- Central Nervous System Infections: Infections such as meningitis, encephalitis, and brain abscesses can cause brain inflammation and damage, leading to seizures.

- Parasitic Infections: Conditions like neurocysticercosis, caused by the pork tapeworm Taenia solium, can lead to epilepsy, particularly in developing countries.

6. Stroke and Vascular Diseases

- Stroke: Strokes that disrupt blood flow to the brain can cause damage and increase the risk of epilepsy.

- Vascular Malformations: Conditions such as arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and aneurysms can increase the risk of seizures if they bleed or cause pressure on brain tissue.

7. Neurodegenerative Diseases

- Alzheimer’s Disease: Individuals with Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases have an increased risk of developing epilepsy.

- Parkinson’s Disease: Though less common, seizures can also occur in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

8. Developmental Disorders

- Autism Spectrum Disorders: Individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are at a higher risk of epilepsy.

- Neurodevelopmental Syndromes: Conditions such as tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and Rett syndrome often have epilepsy as a common symptom.

9. Metabolic Disorders

- Electrolyte Imbalances: Severe imbalances in electrolytes, such as sodium or calcium, can trigger seizures.

- Inherited Metabolic Disorders: Conditions like phenylketonuria (PKU) and mitochondrial diseases can increase the risk of epilepsy.

10. Substance Abuse

- Alcohol and Drug Use: Excessive alcohol consumption, particularly binge drinking, and the use of certain recreational drugs can provoke seizures.

- Withdrawal: Withdrawal from alcohol or drugs, especially benzodiazepines or barbiturates, can increase the risk of seizures.

11. Tumors and Lesions

- Brain Tumors: Both benign and malignant brain tumors can increase the risk of seizures.

- Brain Lesions: Other types of brain lesions, including scar tissue from previous injuries or surgeries, can also be a risk factor.

12. Sleep Deprivation and Stress

- Lack of Sleep: Chronic sleep deprivation can lower the seizure threshold and increase the risk of seizures.

- Stress: High levels of stress and anxiety can trigger seizures in individuals with epilepsy.

Diagnosis of Epilepsy

Diagnosing epilepsy involves a comprehensive evaluation to confirm the presence of recurrent, unprovoked seizures and to determine their cause. The diagnostic process typically includes a detailed medical history, physical and neurological examinations, various diagnostic tests, and sometimes consultation with a specialist. Here are the primary steps involved in diagnosing epilepsy:

1. Medical History

- Detailed Seizure Description: Obtaining a detailed account of the seizures from the patient and witnesses, including the onset, duration, frequency, and characteristics of the seizures.

- Personal and Family History: Reviewing the patient’s medical history, including any previous neurological issues, head injuries, infections, or a family history of epilepsy or other neurological disorders.

- Medication and Substance Use: Identifying any medications, drugs, or alcohol use that could potentially cause or influence seizure activity.

2. Physical and Neurological Examination

- Physical Examination: A general physical exam to assess overall health and identify any signs of conditions that might cause seizures.

- Neurological Examination: A detailed neurological exam to evaluate motor and sensory skills, reflexes, coordination, and mental status. This helps to identify any neurological deficits that could point to an underlying cause of the seizures.

3. Diagnostic Tests

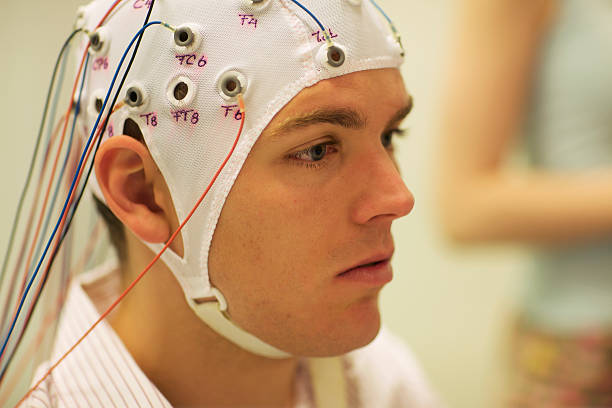

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

- Purpose: Measures electrical activity in the brain and identifies abnormalities that may indicate a tendency for seizures.

- Procedure: Small electrodes are placed on the scalp to record the brain’s electrical activity. The test may include video monitoring and be conducted while the patient is awake, asleep, or exposed to seizure triggers.

- Findings: Abnormal EEG patterns, such as spikes or sharp waves, can support a diagnosis of epilepsy, although a normal EEG does not rule out epilepsy.

Brain Imaging

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Provides detailed images of the brain’s structure, helping to identify any structural abnormalities, tumors, brain damage, or developmental issues that could cause seizures.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Less detailed than an MRI but useful for detecting acute issues like bleeding, tumors, or significant structural changes.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET): Assesses brain metabolism and can help identify areas of the brain with abnormal activity.

- Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT): Evaluates blood flow in the brain and can help locate seizure foci.

Blood Tests

- Purpose: Identify metabolic or genetic conditions that may be causing seizures.

- Tests: May include tests for electrolyte imbalances, blood sugar levels, liver and kidney function, and genetic testing if a hereditary cause is suspected.

4. Neuropsychological Testing

- Purpose: Assess cognitive function and identify any areas of the brain that may be affected by epilepsy.

- Procedure: Involves a series of standardized tests that measure memory, attention, problem-solving, and other cognitive skills.

5. Other Diagnostic Methods

- Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap): May be performed if an infection or inflammatory condition of the brain is suspected. This test involves collecting cerebrospinal fluid to check for signs of infection, inflammation, or other abnormalities.

- Ambulatory EEG: Involves continuous EEG recording over 24-72 hours while the patient goes about their daily activities, helping to capture seizure activity that may not occur during a standard EEG.

6. Referral to an Epileptologist

- Specialist Consultation: In complex cases, or when seizures are difficult to control, a referral to an epileptologist (a neurologist who specializes in epilepsy) may be necessary for further evaluation and management.

Treatment of Epilepsy

The treatment of epilepsy focuses on controlling seizures, minimizing side effects, and improving the quality of life for individuals with the condition. While there is no cure for epilepsy, many people achieve good seizure control with appropriate treatment. Here are the primary approaches to treating epilepsy:

1. Medication

Anti-Epileptic Drugs (AEDs)

- Purpose: AEDs are the mainstay of epilepsy treatment, aiming to reduce the frequency and severity of seizures.

- Common AEDs:

- Carbamazepine (Tegretol)

- Valproate (Depakote)

- Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

- Levetiracetam (Keppra)

- Phenytoin (Dilantin)

- Topiramate (Topamax)

- Clobazam (Onfi)

- Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal)

- Selection: The choice of AED depends on factors such as the type of seizures, age, overall health, and potential side effects.

- Monitoring: Regular blood tests may be necessary to monitor drug levels and check for side effects.

2. Surgical Treatment

Resective Surgery

- Purpose: Remove the area of the brain where seizures originate.

- Types: Temporal lobectomy (most common), focal cortical resection.

- Effectiveness: Can significantly reduce or eliminate seizures in individuals who do not respond to medication.

Laser Interstitial Thermal Therapy (LITT)

- Purpose: A minimally invasive surgical technique using laser technology to destroy the seizure focus.

- Procedure: Involves using MRI guidance to target and ablate the epileptogenic zone.

Corpus Callosotomy

- Purpose: Disconnects the two hemispheres of the brain to prevent the spread of seizures.

- Indication: Used for severe, medication-resistant epilepsy.

Hemispherectomy

- Purpose: Removal or disconnection of one hemisphere of the brain.

- Indication: Reserved for severe cases where seizures originate from one hemisphere, often used in children with conditions like Rasmussen’s encephalitis.

3. Neuromodulation Therapy

Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS)

- Purpose: Delivers electrical impulses to the vagus nerve to reduce seizure frequency.

- Procedure: A device is implanted under the skin in the chest, with wires connected to the vagus nerve in the neck.

Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS)

- Purpose: Monitors brain activity and delivers electrical stimulation to prevent seizures.

- Procedure: A neurostimulator is implanted in the skull, with leads placed at the seizure focus.

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

- Purpose: Delivers electrical impulses to specific brain regions involved in seizure activity.

- Procedure: Electrodes are implanted in the brain, connected to a pulse generator placed under the skin in the chest.

4. Dietary Therapy

Ketogenic Diet

- Purpose: A high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet that can reduce seizure frequency.

- Mechanism: Promotes ketosis, a metabolic state where the body uses fat for energy instead of carbohydrates.

- Indication: Often used for children with medication-resistant epilepsy but can be adapted for adults.

Modified Atkins Diet (MAD)

- Purpose: A less restrictive version of the ketogenic diet, also effective in reducing seizures.

- Diet: Limits carbohydrate intake while allowing more protein than the ketogenic diet.

5. Behavioral and Complementary Therapies

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- Purpose: Helps manage anxiety, depression, and stress, which can trigger seizures.

- Approach: Involves talking therapies to change patterns of thinking and behavior.

Biofeedback

- Purpose: Teaches individuals to control physiological functions, such as heart rate and muscle tension, to reduce seizure frequency.

- Technique: Uses sensors and monitoring devices to provide feedback on physiological processes.

6. Lifestyle and Self-Management Strategies

Medication Adherence

- Importance: Consistently taking prescribed AEDs is crucial for controlling seizures.

- Strategies: Using pill organizers, setting reminders, and establishing a routine.

Avoiding Triggers

- Common Triggers: Lack of sleep, stress, alcohol, flashing lights, and certain medications.

- Management: Identifying and avoiding personal triggers can help reduce seizure frequency.

Regular Sleep Patterns

- Significance: Adequate sleep is essential for brain health and seizure control.

- Recommendations: Establish a regular sleep schedule and create a restful sleeping environment.

7. Emergency Management

Rescue Medications

- Purpose: Quickly stop prolonged or cluster seizures.

- Examples: Diazepam rectal gel (Diastat), midazolam nasal spray (Nayzilam), and lorazepam (Ativan).

Prevention of Epilepsy

While not all cases of epilepsy can be prevented, certain strategies can reduce the risk of developing the condition or mitigate the frequency and severity of seizures for those already diagnosed. Here are key approaches to prevent epilepsy and manage risk factors:

1. Preventing Head Injuries

- Safety Measures: Wearing helmets while biking, skiing, or engaging in contact sports, and using seat belts and child safety seats in vehicles can reduce the risk of traumatic brain injuries.

- Fall Prevention: Implementing safety measures at home, such as removing tripping hazards, using non-slip mats, and installing handrails, can prevent falls, especially in older adults.

2. Managing Prenatal and Perinatal Health

- Prenatal Care: Regular prenatal check-ups and proper nutrition during pregnancy are crucial to reduce the risk of complications that could lead to brain injury in the fetus.

- Avoiding Harmful Substances: Pregnant women should avoid alcohol, smoking, and illicit drugs, as these can harm fetal development and increase the risk of epilepsy.

- Safe Delivery: Ensuring a safe delivery process with appropriate medical intervention can prevent birth-related injuries.

3. Preventing Infections

- Vaccinations: Keeping up-to-date with vaccinations, such as those for meningitis and encephalitis, can prevent infections that may cause brain inflammation and lead to epilepsy.

- Hygiene Practices: Maintaining good hygiene and taking measures to avoid infections, such as proper handwashing and avoiding contact with sick individuals, can reduce the risk of infections that might lead to epilepsy.

4. Managing Chronic Conditions

- Cardiovascular Health: Managing conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol can prevent strokes and other vascular issues that may lead to epilepsy.

- Regular Check-Ups: Regular medical check-ups and appropriate management of chronic conditions can prevent complications that could trigger seizures.

5. Reducing Substance Abuse

- Avoiding Alcohol and Drugs: Limiting alcohol consumption and avoiding recreational drugs can reduce the risk of seizures and the development of epilepsy.

- Medication Compliance: Adhering to prescribed medications and avoiding abrupt withdrawal from drugs that can cause seizures, such as benzodiazepines, can help prevent seizure onset.

6. Genetic Counseling

- Family Planning: For individuals with a family history of epilepsy or genetic conditions associated with seizures, genetic counseling can provide information on risks and preventive measures.

- Early Detection: Identifying and managing genetic conditions early can help reduce the risk of developing epilepsy.

7. Healthy Lifestyle Choices

- Balanced Diet: A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats supports overall brain health.

- Regular Exercise: Engaging in regular physical activity promotes cardiovascular health and can help prevent conditions that might lead to epilepsy.

- Stress Management: Reducing stress through techniques such as meditation, yoga, and mindfulness can help prevent stress-induced seizures.

8. Monitoring and Managing Epilepsy

- Medication Adherence: Consistently taking prescribed anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) can prevent breakthrough seizures and reduce the risk of status epilepticus.

- Regular Follow-Up: Regular visits to a neurologist for monitoring and adjustment of treatment plans can help manage epilepsy effectively and prevent complications.

- Seizure Triggers: Identifying and avoiding personal seizure triggers, such as lack of sleep, stress, flashing lights, and certain foods or medications, can reduce seizure frequency.

9. Awareness and Education

- Public Education: Raising awareness about epilepsy and its risk factors can lead to early intervention and better management of the condition.

- Patient Education: Educating individuals with epilepsy and their families about the condition, treatment options, and lifestyle modifications can empower them to manage the condition effectively.

Related Conditions to Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent seizures, but several other conditions can mimic or coexist with epilepsy, complicating diagnosis and treatment. Understanding these related conditions is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management. Here are some key conditions related to epilepsy:

1. Febrile Seizures

- Definition: Seizures triggered by fever, typically occurring in young children.

- Symptoms: Generalized tonic-clonic seizures lasting a few minutes, often during a high fever.

- Prognosis: Most children outgrow febrile seizures and do not develop epilepsy.

2. Non-Epileptic Seizures (NES)

- Definition: Seizures that resemble epileptic seizures but are not caused by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Also known as psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES).

- Causes: Often linked to psychological factors, such as stress, trauma, or psychiatric disorders.

- Diagnosis: Requires video-EEG monitoring to distinguish from epileptic seizures.

- Treatment: Focuses on addressing underlying psychological issues through therapy and counseling.

3. Syncope

- Definition: Temporary loss of consciousness due to a sudden drop in blood pressure, leading to reduced blood flow to the brain. Also known as fainting.

- Symptoms: Sudden onset, brief loss of consciousness, and quick recovery.

- Diagnosis: Distinguished from seizures by the absence of postictal confusion and through cardiovascular assessments.

- Treatment: Addressing the underlying cause, such as dehydration, heart issues, or vasovagal syncope.

4. Migraines

- Definition: Severe, recurrent headaches often accompanied by other neurological symptoms.

- Symptoms: Throbbing headache, nausea, sensitivity to light and sound, and in some cases, aura (visual or sensory disturbances).

- Overlap with Epilepsy: Both conditions can present with aura and sensory disturbances, but migraines typically do not involve loss of consciousness.

- Treatment: Medications to prevent and relieve migraines, lifestyle changes, and managing triggers.

5. Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIAs)

- Definition: Brief episodes of neurological dysfunction caused by temporary loss of blood flow to the brain.

- Symptoms: Similar to a stroke, including sudden weakness, numbness, difficulty speaking, and vision changes, but symptoms resolve within minutes to hours.

- Risk Factors: Similar to those for stroke, including hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

- Treatment: Addressing risk factors and preventing future strokes through lifestyle changes and medications.

6. Sleep Disorders

- Sleep Apnea: Characterized by repeated interruptions in breathing during sleep, leading to fragmented sleep and daytime fatigue. Sleep deprivation from sleep apnea can trigger seizures in individuals with epilepsy.

- Narcolepsy: A condition marked by excessive daytime sleepiness and sudden loss of muscle tone (cataplexy), which can sometimes be mistaken for seizures.

- Diagnosis: Sleep studies (polysomnography) and multiple sleep latency tests (MSLT).

- Treatment: Managing the sleep disorder through continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for sleep apnea or medications for narcolepsy.

7. Movement Disorders

- Tics and Tourette Syndrome: Involuntary, repetitive movements or vocalizations. These can be mistaken for seizures but typically do not involve loss of consciousness.

- Essential Tremor: A common movement disorder causing rhythmic shaking, usually in the hands. Unlike seizures, essential tremor does not involve changes in consciousness.

- Diagnosis: Clinical evaluation and observation of symptoms.

- Treatment: Medications, behavioral therapy, and sometimes deep brain stimulation (DBS).

8. Psychiatric Conditions

- Panic Attacks: Sudden episodes of intense fear and physical symptoms such as palpitations, sweating, and shortness of breath, which can mimic seizures.

- Conversion Disorder: Neurological symptoms that cannot be explained by medical conditions, often related to psychological stress.

- Diagnosis: Comprehensive psychiatric assessment and excluding other medical conditions.

- Treatment: Psychological therapies, medications, and managing underlying psychiatric conditions.

9. Stroke

- Definition: A sudden interruption in blood supply to the brain, causing brain damage.

- Symptoms: Sudden weakness or numbness, especially on one side of the body, difficulty speaking, vision changes, and loss of balance.

- Overlap with Epilepsy: Seizures can occur as a result of a stroke.

- Treatment: Emergency medical treatment, medications to prevent further strokes, and rehabilitation.

Living With Epilepsy

Living with epilepsy involves managing a complex condition that can significantly impact various aspects of daily life. However, with proper medical care, lifestyle adjustments, and support, individuals with epilepsy can lead fulfilling lives. Here are key strategies and considerations for living with epilepsy:

1. Medical Management

Medication Adherence

- Consistent Use: Taking anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) as prescribed is crucial for controlling seizures.

- Regular Monitoring: Regular check-ups with a healthcare provider to monitor drug levels and adjust medications as needed.

- Managing Side Effects: Communicating any side effects to a healthcare provider to adjust treatment plans accordingly.

Regular Medical Check-Ups

- Neurologist Visits: Regular appointments with a neurologist to review seizure activity, medication effectiveness, and any new symptoms.

- General Health Maintenance: Routine health screenings and preventive care to manage overall health.

2. Lifestyle Modifications

Identifying and Avoiding Triggers

- Common Triggers: Lack of sleep, stress, flashing lights, alcohol, and certain medications.

- Personal Triggers: Keeping a seizure diary to identify individual triggers and patterns.

Healthy Lifestyle Choices

- Balanced Diet: Eating a nutritious diet to support overall health and well-being.

- Regular Exercise: Engaging in safe physical activities to improve physical and mental health. Consult with a healthcare provider for recommendations.

- Adequate Sleep: Ensuring regular and sufficient sleep to reduce seizure risk.

3. Safety Precautions

Home Safety

- Environment Modifications: Making the home safer by removing tripping hazards, using protective covers for sharp corners, and ensuring easy access to help.

- Shower vs. Bath: Taking showers instead of baths to reduce the risk of drowning during a seizure.

Seizure Preparedness

- Seizure Response Plan: Developing a plan for what to do during and after a seizure, including when to seek emergency help.

- Medical Alert: Wearing a medical alert bracelet or carrying a medical ID card that provides information about the condition and emergency contacts.

4. Driving and Transportation

- Driving Regulations: Adhering to local laws and regulations regarding driving with epilepsy. Some areas require a certain period of seizure-free time before driving is allowed.

- Alternative Transportation: Utilizing public transportation, ride-sharing services, or relying on friends and family for transportation needs.

5. Work and Education

Workplace Accommodations

- Disclosure: Deciding whether to inform employers about the condition to receive necessary accommodations.

- Accommodations: Requesting reasonable accommodations, such as flexible work hours, breaks, or modifications to the work environment.

Educational Support

- Individualized Education Plan (IEP): For students with epilepsy, working with educators to create an IEP that addresses specific needs and accommodations.

- Seizure Action Plan: Developing a plan with school staff to manage seizures and ensure safety during school hours.

6. Emotional and Psychological Support

Mental Health Care

- Counseling: Seeking therapy or counseling to address anxiety, depression, or other emotional challenges associated with epilepsy.

- Support Groups: Joining epilepsy support groups to connect with others who understand and share experiences and coping strategies.

7. Social and Recreational Activities

- Inclusive Participation: Engaging in social and recreational activities with appropriate precautions to maintain a fulfilling and active lifestyle.

- Educating Friends and Family: Informing friends and family about epilepsy and how they can support and respond during seizures.

8. Emergency Preparedness

- Rescue Medications: Keeping rescue medications, such as diazepam rectal gel or midazolam nasal spray, readily available to stop prolonged seizures.

- Emergency Contacts: Having a list of emergency contacts and medical information easily accessible.

9. Planning for the Future

Legal and Financial Planning

- Advance Directives: Establishing advance directives, including a living will and durable power of attorney for healthcare and finances.

- Financial Planning: Working with a financial advisor to manage expenses related to epilepsy care and long-term needs.

Conclusion

While epilepsy can be a challenging condition to live with, understanding and addressing the multifaceted aspects of the disorder can lead to better management and improved quality of life. With advancements in medical research and treatment options, there is hope for even better outcomes in the future. By staying informed, proactive, and connected with healthcare providers and support networks, individuals with epilepsy can navigate their journey with confidence and resilience.

Through education, awareness, and comprehensive care, we can work towards a world where individuals with epilepsy are understood, supported, and empowered to live their lives to the fullest.